Collector’s Guide: Seven things to know about Henry Moore

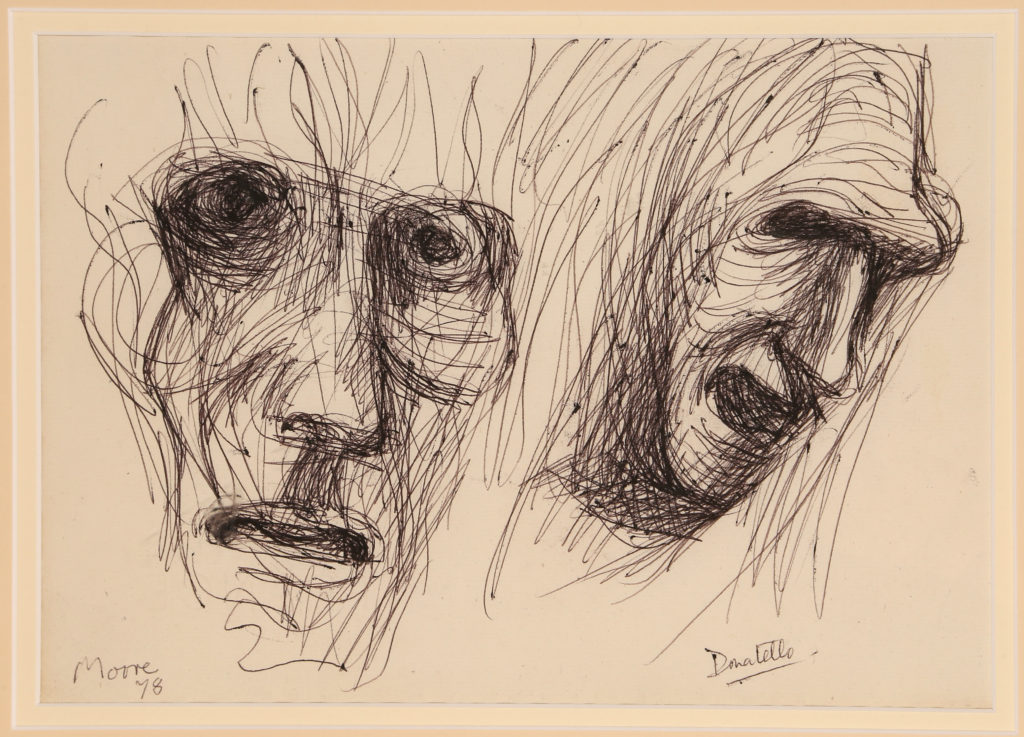

Henry Moore, 1898-1986, 'Donatello', 1978, pen black ink, titled, signed

and dated front, (19 x 27cm). Estimate: £7000 - £9000.

Ahead of the 20th Century & Contemporary Art & Design auction on 23rd January, we take a closer look at the work of esteemed British sculptor Henry Moore (1898 – 1986), who pursued the aesthetic questions of form and shape and the affinity between human beings and the landscape throughout his career.

Moore was the seventh child of a Yorkshire coal miner

Encouraged by his father, Moore trained to be a teacher and worked at the grammar school that he had attended in Castleford, Yorkshire. His pursuit of higher education pleased his father, who hoped that his children would not work in the mines. As a result, he was greatly disappointed when Moore made the decision to become a sculptor, which he considered as manual labour.

Moore was gassed at the Battle of Cambrai on 30th November 1917

As a result of Moore’s war service, he was entitled to an ex-serviceman’s grant. Following the war, Moore enrolled at the Leeds School of Art where he was given a sculpture studio and granted access to the private collection of the University Chancellor Sir Michael Sadler. During his time at Leeds School of Art, Moore was first exposed to Modernism and he also met Barbara Hepworth, who would become a lifelong friend and professional rival.

Moore’s move to London marked a turning point in his artistic direction

‘Even when I was a student I was totally preoccupied by sculpture in its full spatial richness, and if I spent a lot of time at the British Museum in those days, it was because so much of the primitive sculpture there was distinguished by complete cylindrical realisation.’ – Henry Moore, 1955

Moore was awarded a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in London in 1921, which bought him closer to the ethnographic collections on display in the Victoria & Albert Museum and the British Museum. This period would prove pivotal to his aesthetic; the themes of the mother and child and the reclining figure superseded the Victorian romanticism that prevailed in his work and would become key sculptural motifs.

Moore used the revolutionary technique of direct carving in the 1920’s

Inspired by the work of Constantin Brancusi, Jacob Epstein, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska and Frank Dobson, Moore and other Royal College sculptors, including Hepworth and her first husband John Skeaping, deployed the avant-garde method of direct carving. Based on the concept of ‘truth to materials’, direct carving plays on the natural flaws found during the carving process and involves cutting into marble or wood without using maquettes or clay modelling in preparation.

In 1940, after Henry and Irina Moore’s home in London was damaged in the Blitz, they settled at Hoglands in Perry Green, Hertfordshire. The farmhouse is now home to the Henry Moore Foundation

Like many other artists, Moore left London after the war and settled in the countryside. Moore and his wife would remain in Hoglands for the rest of their lives. By the 1950s, Moore was completing commissions for substantial outdoor sculptures including outside the Paris UNESCO building and in London’s Parliament Square. By the late 1970s, Moore’s work had been shown in countless exhibitions and in 1977, the Henry Moore foundation was established to celebrate his life and work.

A younger generation of sculptors challenged Moore’s ideals

During the 1950’s, sculptors such as Giacometti and Germaine Richier were preoccupied with man’s post-war existential crisis. Inspired by this feeling and as a riposte to Moore and Hepworth, a group of young sculptors including Reg Butler, Lynn Chadwick and Kenneth Armitage participated in the influential New Aspects of British Sculpture exhibition at the British Pavilion of the 1952 Venice Biennale. In response, Moore created a series of family groups intended as a compassionate and unifying response to the atrocity of war.

Commissions gave Moore a public presence in the USA that was unprecedented for a foreign living sculptor

Moore’s appeal in the States proved unprecedented during the post-war and Cold War years. His monumental bronzes, which were both not entirely figurative or abstract, proved popular in the context of public sculpture because they provided highly conspicuous symbols of leadership and citizenship.

In 1967, art critic Hilton Kramer wrote about the demand for Moore’s work, ‘…massive but gentle forms, its bronze glitter and high-style rhetoric, its quality of being at once eminently modern and yet vaguely traditional – that makes it the inevitable choice of civic-minded patronage. Not every such patron manages to get himself a Moore, but everyone seems to want one.’