Chinese Export Silver is perhaps an unfamiliar area of fine silver for some European and western buyers and collectors, but Chinese silversmithing in the western manner has a long history, concurrent with much fine European silversmithing and producing items of great quality and high technical achievement. Here at Chiswick Auctions we have been delighted to offer to the market a number of significant and interesting items of Chinese Export Silver in our past sales and will feature several items in our next sale in October.

Starting in earnest from the very end of the 18th century the ‘China Trade’ period saw the arrival in the UK and Europe from China items of silver in forms that mirrored western silversmithing forms, such as salts, flatware, teapots, mugs, egg cruets and so on. In imitation of British style hallmarks these items were ‘marked’ with ‘pseudo marks’, often containing a mark for the company supplying the item, not the maker (or manufacturer) of the item.

An early 19th century Chinese Export silver teapot stand, Canton circa 1820 mark of Tu Hopp

pseudo hallmarks of a lion passant, duty mark, leopards head and a T

sold for £938 incl. premium

However, from the middle of the 19th century a new style of silverware emerged, with distinctly ‘Chinese’ aesthetics employed in styling and applied decoration; these items also started to display Chinese character marks in place of the ‘pseudo marks’ of previous decades. A documented example of this transition is ‘The Celestial Cup’ (S&J Stodel) that was exhibited at the 1851 Great Exhibition and is recorded in Robert Hunt’s handbook to the event: ‘Two silver cups, the Celestial Cup presented at Hong Kong Races, 1850 and a smaller cup of silver… are shown among the Chinese contribution…’. This trophy utilises the dragon form handles so distinctive to Chinese Export silver while being marked with pseudo marks and the KHC for Khecheong, the supplier or retailer.

Although used for Hong Kong races, the Celestial Cup and many others would have been produced in Canton. Canton was the primary area for the production of silverware, benefiting from its geographical proximity to major trading ports such as Hong Kong and Macau with their efficient links to Britain, the European powers and their colonies as well as to the USA. Throughout the second half of the 19th and into the middle of the 20th century production of Chinese Export Silver grew, and more areas of production developed, some with their own distinctive regional styles; many others following the ever-changing Western fashions in decorative patterns and forms, as these came and went.

A mid to late 19th century Chinese export silver double gourd tea caddy or wine bottle, Canton circa 1870 retailed by Cum Shing

artisan mark SHEN CHANG 慎昌

sold for £2,125 incl. prem

An early 20th century Chinese export silver three-piece tea service, Shanghai circa 1910

retailed by Luen Hing

artisan mark YU JI 敔 記

sold for £2,375 incl. prem

An early 20th century Chinese Export silver tray, Tianjin circa 1920 retailed by Ye Ching Company

Marked STERLING and Y.C.C

sold for £1,000 incl. prem

A mid-20th century Chinese export silver four-piece tea and coffee service, Hong Kong circa 1940 retailed by Tack Hing

marked TACKHING, MADE IN H.K. STERLING W

sold for £2,250 incl. prem

A pair of early 20th century Chinese Export silver vases, Jiujiang circa 1900 by Tu Qing He

Each marked 和慶涂

sold for £1,000 incl. prem

An early 20th century Chinese Export silver sauce boat, Beijing circa 1930 by Sheng Yuan

Marked 聲元

sold for £188 incl. prem

When valuing Chinese Export Silver it is important to try to the identify the makers, production locations and dates of making of items and this is helped by understanding the marks used in silversmithing from approximately 1860 to 1950. These marks can be in Chinese text, in western / Latin characters or can use a combination of both.

For the European market marks were made in items for the retailers of wares using Latin lettering – Retailers’ Marks. However, these Retailers’ Marks are not ‘maker’s marks’ as found on British silver, and this has led to a persistent mis-attribution of an item’s production, and therefore the merit of that item’s craftsmanship

The most frequently encountered Retailer’s Mark in Chinese Export Silver is WH, for Wang Hing, a highly successful retail business operating in Canton from the 1860s that opened a Hong Kong branch in the early 20th century. As with other Retailer’s Marks, items of Chinese Export Silver bearing the WH mark (in its many forms) were never made by Wang Hing himself, nor was he responsible for the production of marked pieces in his own workshop – he was the retailer of the items alone. , to a retailer (based on a Retailer’s Mark) rather than to a silversmith or ‘maker’ of an item.

Crucially, Chinese Export Silver was never subject to a formal system of assay, as was the case in the UK. So, these Retailers’ Marks are not hallmarks, nor assay marks, but marks placed on items for sales and stock purposes. In addition to these Latin letters, there are usually Arabic numerals, often 90 or 85, that may be separate punches or integral to the Retailer’s Mark and allude to the purity of the silver, but as no system of assay was in place in China at the time these cannot be taken as an indication of the actual purity of the silver used in an item.

The silver retailers operated in a variety of locations but would sell silver made in many different regions - so not necessarily from silversmiths working in the retailer’s own region. It is thus the identity of the Artisan’s Mark that confirms the region where an item was produced, not the marks placed on by the retailer – read on!

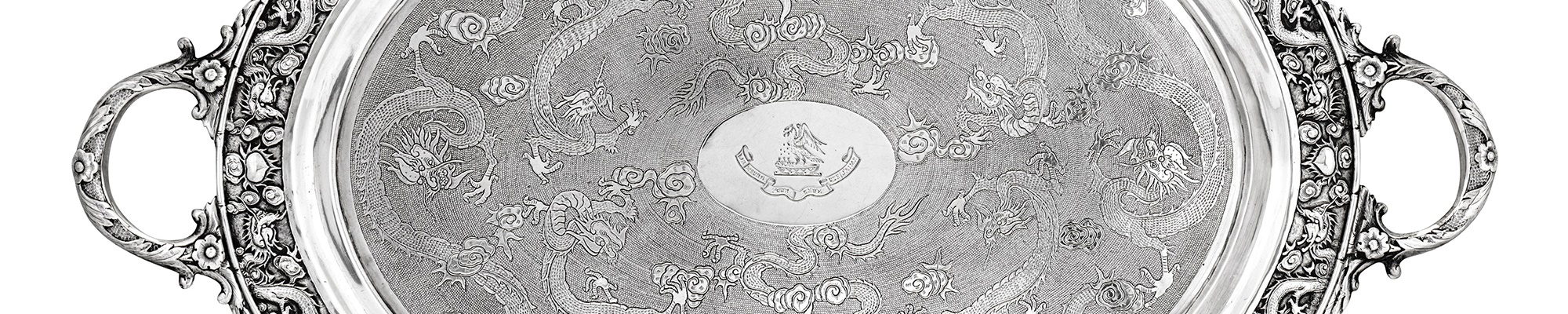

A late 19th / early 20th century Chinese Export silver bowl, Canton circa 1900 retailed by Luen Wo

Marked underneath SHANGHAI, LUEN.WO and with artisan mark QIU JI 求記 (a Canton workshop)

sold for £1,188 incl. prem

A late 19th / early 20th century Chinese Export silver biscuit box, Shanghai circa 1900 retailed by Luen Wo

Marked underneath with retailer’s mark LW twice and artisan mark HU ZHEN 華珍 (a Shanghai workshop)

sold for £1,750 incl. prem

Unlike the Retailer’s Mark, the Artisan’s Mark was stamped on items by the actual workshop responsible for producing the item of silverware and uses Chinese characters. This Artisan’s Mark is the closer to the ‘maker’s mark’ found on Western silver, but a particular Artisan’s Mark does not necessarily infer the workmanship of that one named silversmith alone, in the same way that the name Wedgwood on a ceramic item guarantees that Josiah Wedgwood threw that pot. For any silversmithing workshop the capacity and skills required to produce the quantity of silver that still survives today required a full team of artisans, each with their own particular skill set, such as raising, embossing, piercing and so on.

Many Artisans’ workshops supplied more than one retailer and thus the list of artisan marks is rather extensive most are English transliterations from Mandarin Chinese but Cantonese versions also occur, such as 大吉 (Mandarin Da Ji, Cantonese Tai Kut). If these marks remain essentially anonymous, taking the name of the leading Artisan rather than other colleagues involved with the production of the pieces, there are exceptions where some Artisan’s Marks are found on such high quality and excellently produced items that one can deduce that these workshops were acting at the height of the trade at the time.

One such example is the Canton based workshop mark for遂昌 (Sui Chang) Retailer WH for Wang Hing, workshop or artisan mark for 遂昌 (Sui Chang), numeral 90

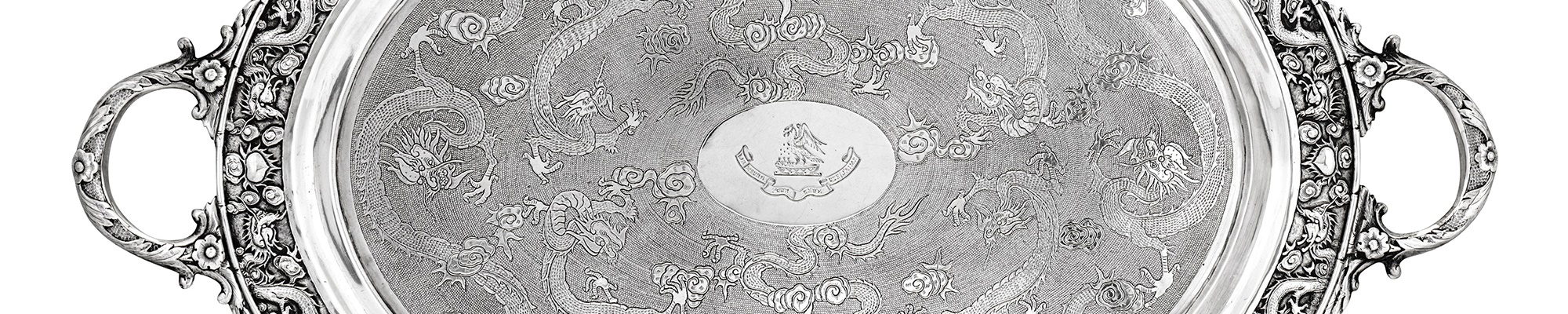

This particular Artisan’s Mark is found on a number of high-quality pieces, from the small to the large, including many finely pierced items. Recently, a large tray of some 116 troy ounces. The tray was of oval form was flanked by cast and applied handles leading to a broad rim embossed with trailing Chinese dragons amidst clouds; the field of the tray flat was chased with decoration of more Chinese dragons all against a finely matted or stippled ground altering the surface and its reflections against the plain polished areas. The British armorial crest engraved on the piece can be attributed to Scotsman Charles James George Paterson (1858 – 1937) whose obituary paints a picture of a man interested in worldly things, fitting for such a magnificent tray.

A large late 19th / early 20th century Chinese Export silver twin handled tray, Canton circa 1900, retailed by Wang Hing

Marked to the reverse with retailer’s mark of WH, 90 and workshop artisan mark 遂昌 (Sui Chang)

Sold for £5,250 incl. premium

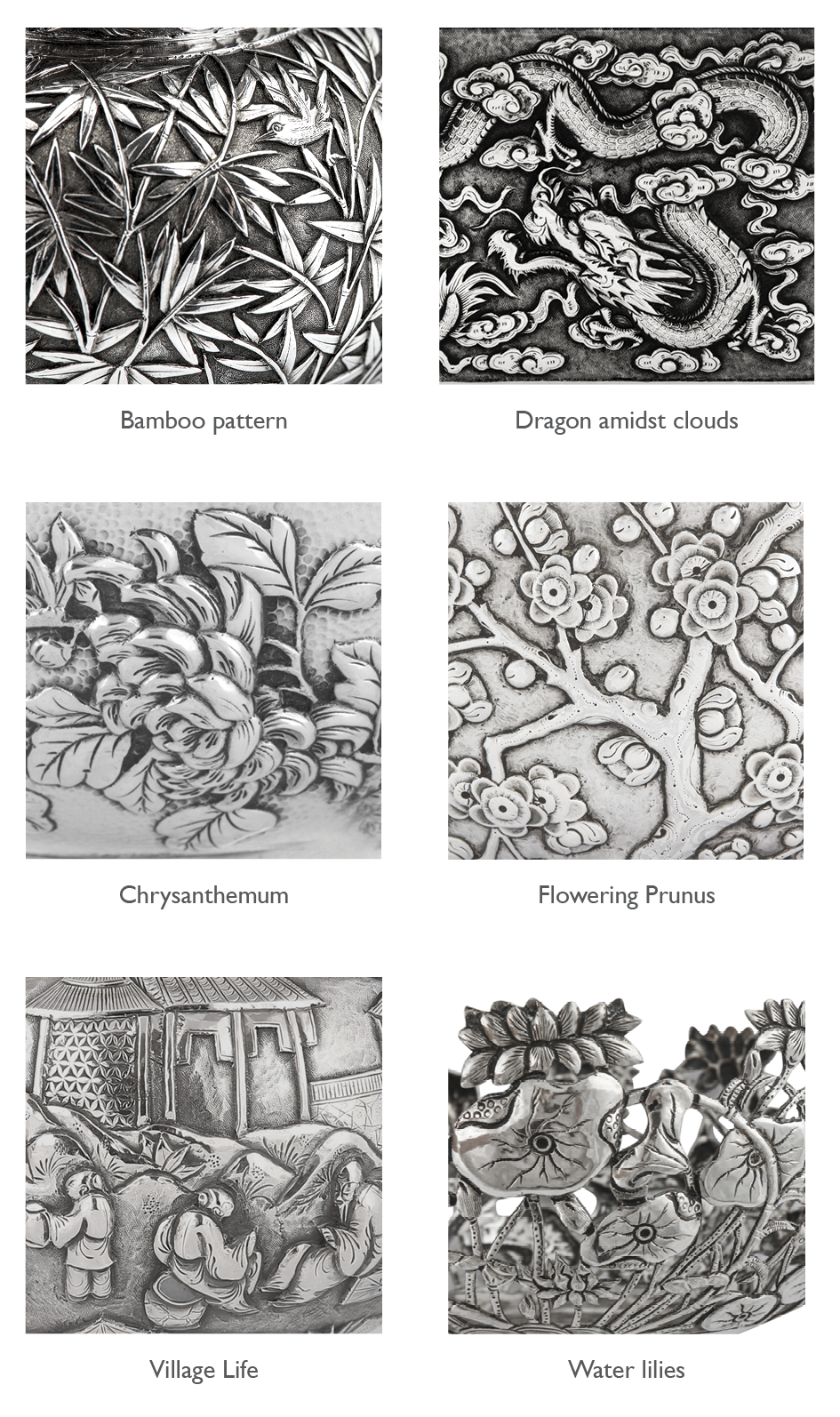

Another prominent Artisan’s Mark is of a workshop whose items are of excellent quality and which are found in conjunction with many different Retailers’ Marks – this is the Canton-based 求記 (Qiu Ji). Their Artisan’s Marks are often to be found on items featuring finely pierced and embossed workmanship, as well as trays with deftly executed engraved and flat chased scenes, such as village life or cranes. One such tray shown below, was sold by Chiswick Auctions in 2021, with a particularly well-worked field depicting scenes of Chinese village life, with people surrounded by buildings, rocky out crops, bamboo and willow trees. All of this was set against a tightly and uniformly worked ring-punched ground, allowing the figural elements to proudly stand out in high contrast. This particular tray came with significant provenance, starting with it being owned by Thomas Child (1841-1898), an English photographer and engineer best known for his pioneering photography work in China. Child produced a large body of photographs during his time in Beijing in the 1870s and 1880s, a time when virtually no other photographers operated in the city.

A late 19th century Chinese Export silver twin handled tray, Canton circa 1890 retailed by Wang Hing

Marked to the reverse with WH, numeral 90 and artisan mark 求記 (Qiu Ji)

Sold for £5,500 incl. premium

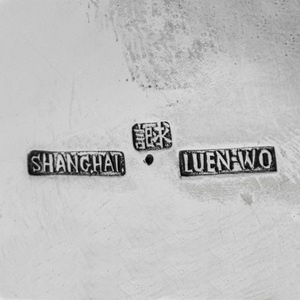

Chinese Export silver utilised recurring and familiar motifs and decorative patterns across a wide range of forms and, just as with Japanese, Persian and Indian silver of the same period, this development of a distinctive style and appearance has meant that certain patterns and techniques have come to be the most recognisable visual vocabulary associated with Chinese Export Silver, helping to define this distinctive body of work.

In the production of Chinese Export Silver embossing was especially popular, regularly combined with piercing to create a third dimension from a flat sheet of metal. Also popular was the time-consuming and costly process of cast and applied decoration, a technique that enables effects to be created that resemble embossing but are of especially high quality, so that items with this form of decoration deservedly command higher prices.

In this technique the decoration is worked from the interior of the item (to be seen externally), called repoussé, and this is then additionally worked from the outside of the item the combination of the two being termed embossing.

Here, the decoration is first formed separately as a casting then applied as a solid piece to the body of the item of silver –the decoration is not worked from the body of the silver item itself.

The metal is embossed as above to create the decorative elements then the areas of unworked metal are removed by saw cutting. The piercing of silver should not be confused with reticulation, which is an arrangement of lines forming a net-like pattern on ceramics and resembles piercing.

This technique creates the design by using a special chasing hammer on the surface of the metal to build up a sequence of lines of varying depth; while this produces designs that resemble engraving no metal is removed by this process whereas engraving does scrape out part of the surface.

Using a small hammer to repeatedly strike the surface of the metal, a fine texture of marks and indentations is created, altering its visual reflectivity. This technique was especially popular on Shanghai-made pieces of the 1920s-40s.

This technique takes sheet metal which is cut and bent into shape, chased, and then applied to cast elements. In particular this is used on the frills of cast dragons heads, where the horns are made from extruded wire cut and soldered together.

Dr Adrien Von Ferscht is the leading scholar in the study of Chinese export silver and its marks, publishing this research in the online third edition of Chinese Export Silver – the definitive collector’s guide (2015). We are grateful to Dr Adrien for the generous support given to the department over the years with aid to cataloguing and identifying marks for Chinese Export silver.

For further examples of Chinese Export silver, but with outdated mark attributions, see:

Forbes, Crosby, H.A., Devereux Kernan, J., & Wilkins, R.S. (1975) Chinese Export Silver 1785 to 1885. Massachusetts: Museum of the American China Trade.

Also:

Devereux Kernan, J. (1985) The Chait Collection of Chinese Export Silver. New York: Chait Gallery