Discovery of final oil painting by Rex Whistler (1905 – 1944)

Rex Whistler (1905-1944) Binderton House, West Sussex, 1944 oil on Rowney canvas board. 30.4cm x 40.3cm. Estimate: £2,500 - £3,000.

Rex Whistler (1905-1944) Binderton House, West Sussex, 1944 oil on Rowney canvas board. 30.4cm x 40.3cm. Estimate: £2,500 - £3,000.

Following the success of yesterday evening's Chiswick Lates, which saw Rohan McCulloch, Early British Paintings & Drawings Specialist, discuss 'An important discovery in a cupboard under the stairs', we take a further look at a previously unseen work by Reginald John ‘Rex’ Whistler discovered in Earls Court that is offered in the auction of British & European Fine Art with Portrait Miniatures on 12th December. Dr. Nikki Frater, Whistler expert and advisor to the Salisbury Museum, believes this work to ‘his last painting in England and indeed probably his last oil ever.’ Contemporary view of Binderton House. Courtesy of Rightmove, 2015.

Contemporary view of Binderton House. Courtesy of Rightmove, 2015.

The house depicted in the work has been confirmed as Binderton House – the private residence of Sir Anthony Eden who was the British Foreign Secretary at the time before later becoming Tory Prime Minister. A friend of Eden’s, Whistler was a regular guest at Binderton, and is known to have painted the house in early July 1944 just before he departed for Normandy with the Tank Battalion of the Welsh Guards.

By the age of 22, Whistler had completed a commission for the restaurant at the Tate Gallery, producing a series of playful and eccentric murals that quickly gave him celebrity status. The room became described as ‘the most amusing room in Europe’ and is now known as The Rex Whistler Restaurant.

It is said that Evelyn Waugh based the artist Charles Ryder in Brideshead Revisited, (1945) at least in part, on Whistler – the modest, naturally talented and charming middle-class boy drawn into the enchanting albeit emotionally perilous country-house society. Whistler was a frequent guest of distinguished society and often painted the grand homes of his hosts. This stratum of upper-class society included the Sitwells, Lord Berners, Nancy Mitford, Cecil Beaton, Oliver Messel, Stephen Tennant and other ‘Bright Young Things’ who embodied the ‘between time’, which saw the conventions of Edwardian society abandoned in favour of a new freedom.

Described by close friend Cecil Beaton as ‘enchantingly funny’, Whistler belonged to this ultra-sophisticated inter-war generation who knew that they were living on borrowed time. It was the delicacy, wit and artifice in Whistler’s work that viewers admired, because it turned its back on reality.

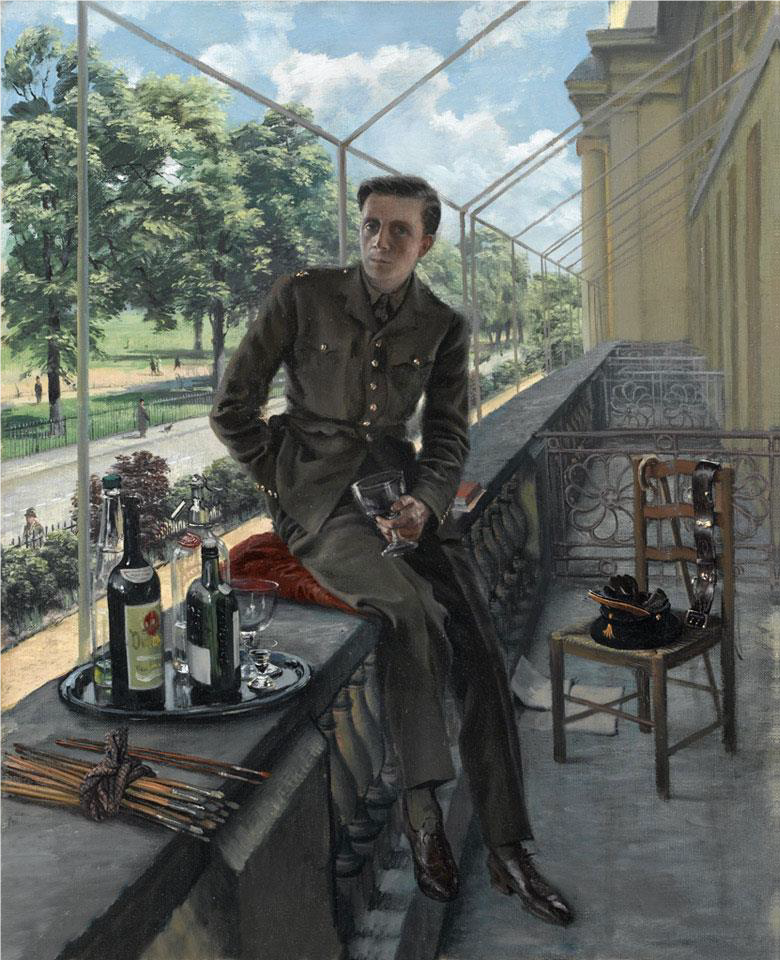

On the 18th of July, on his first day of active service as a Tank Commander as part of Operation Goodwood, Rex Whistler was killed in action near Caen. Rex Whistler, self-portrait in Welsh Guards uniform, 1940. Courtesy of the National Army Museum, London.

Rex Whistler, self-portrait in Welsh Guards uniform, 1940. Courtesy of the National Army Museum, London.

A self-portrait in the National Army Museum in London shows Whistler, in his Welsh Guards’ uniform, perched on the balcony of a house in York Terrace, overlooking Regent’s Park. Aged 35 at the time of this portrait, Whistler was too old for immediate conscription and instead volunteered for service upon the outbreak of war.

By this time, Whistler boasted a reputation as a celebrated and diverse artist recognised for his revealing society portraits, fantastical murals, imaginative set designs and book illustrations.

Upon news of his death, The Times newspaper reportedly received more letters about Whistler than any other victim of the war.

‘Now his potentials were all unfulfilled, and Rex the person, suffused with effortless charm…would never grow old.’ – Cecil Beaton

The glamour and frivolity of the country estate – the setting of ‘the long weekend’ so much enjoyed by the likes of Whistler, Beaton, Nancy Mitford and Evelyn Waugh – was at odds with the new reality faced by Post-War Britain. Whistler’s Binderton House serves as an inadvertent tribute to an era consigned to letters and history past.