31st Oct, 2023 11:00

Islamic Art - Property of a European Collector Part VI

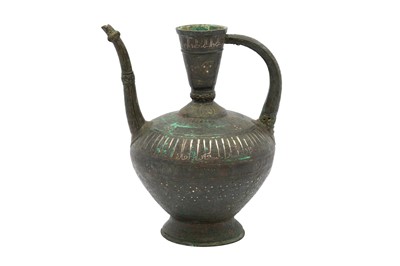

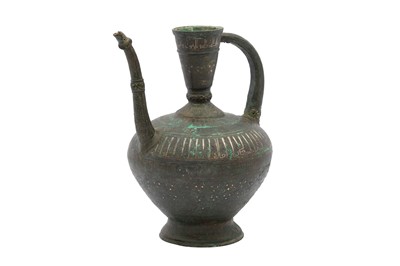

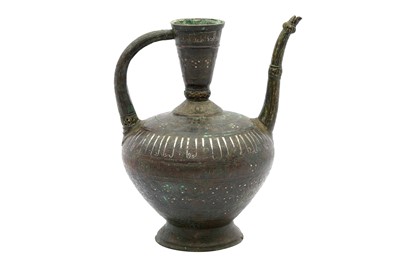

AN IMPRESSIVE FINELY ENGRAVED SILVER-INLAID BRONZE CEREMONIAL SPOUTED EWER

Herat, Khorasan, Eastern Iran, ca. 1180 - 1220

AN IMPRESSIVE FINELY ENGRAVED SILVER-INLAID BRONZE CEREMONIAL SPOUTED EWER

Herat, Khorasan, Eastern Iran, ca. 1180 - 1220

Of pyriform shape, resting on a short splayed foot, rising to broad shoulders and a tall conical neck with a splayed base, the sides embellished with a curved handle and a gently upward-turned spout, the exterior densely engraved with overlapping epigraphic bands in-filled with foliated, knotted and monumental Kufic and naskhi scripts with Arabic prayers, blessings, and religious invocations, two bands inlaid in silver, all of them set against vegetal scrollwork, interspersed amidst silver-inlaid rosette roundels and strapwork friezes, the base of the curved handle and neck featuring an openwork vegetal scrollwork motif repeated on the spout in engraved form, 30.4cm high.

Until the Mongol conquest of Iran (1219 - 1258), Herat was a thriving, undisputed centre of production for Persian metalware showcasing supreme quality of casting, fineness of engraving, and excellent inlays in silver and copper. In Islamic art, Herati vessels were, and still are celebrated as one of the most accomplished forms of Iranian metalwork, and the present ewer is no exception. Its pear-shaped body, tall neck, and curved handle echo Mediterranean traditions rooted in Roman antiquity, but its decorative program is closely affiliated with the traditional arts of Medieval Iran. The powerful combination of these two elements provided the future generations of metal artisans, in particular the ones working in Mosul and the Jazira region, with a fertile and long-lasting inspirational model, embodied in some of the most well-known, prestigious vessels in Islamic art now part of major museums' collections like the Blacas ewer (British Museum, inv. no. 1866,1229.61), the Homberg ewer (Keir Collection, Dallas Museum of Art, inv. no. K.1.2014.82), and the ewer made for Mahmud b. Sinjar Shah (r. 1208 - 1250/51), the Zangid atabeg (governor) who ruled Jazirat Ibn 'Umar (MIA, Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, inv. no. MW.466.2007).

In terms of decoration, the wide central band of silver-inlaid rosette roundels links this lot to another important Herati metal masterpiece: the candlestick base with repoussé lions and ducks at the Louvre Museum (inv. no. OA 6315, published in A. Collinet, Précieuses Matières: les Arts du Métal dans le Monde Iranien Médiéval, 2021, cat. 3, pp. 116 - 121). However, the noticeable lack of figural decoration in our ewer should not mislead the beholder into thinking this was a lesser production. On the contrary, the lively figures and animal motifs that occasionally decorated Herati metals (see for instance the large astrological basin sold at Sotheby's London, 31 March 2021, lot 74) have been here traded for several overlapping epigraphic bands in a variety of Arabic scripts, including monumental and floriated Kufic and angular naskhi. The mastery to achieve this degree of calligraphic variety on metal is remarkable and is not necessarily less compelling than a figural courtly cycle. The calligraphic band around the shoulders of the present lot shows a degree of similarity with the inscription around the rim of a lidded vase in the Khalili Collection of Islamic Art (inv. no. MTW 1361, published in J. M. Rogers, The Arts of Islam: Masterpieces from the Khalili Collection, 2010, cat. 107, p. 98). Perhaps though, the most interesting feature of this ewer is the content of its inscriptions. Indeed, the several Arabic prayers and auspicious blessings on this lot's body and neck could shed light on its specific ceremonial use in a religious ritual setting, where figures and animals would have not been welcomed due to the rules of Islamic iconoclasm. This assumption offers interesting food for thought.

Ewers of this shape and design have always been associated with courtly gatherings, used either to serve water, wine, and other beverages during special festivities or to wash the guests' hands upon their arrival. The practice of washing hands as an act of purification is closely connected with the typical Muslim ritual of going through a bodily ablution (wudu) before starting the salah (or namaz, the five daily prayers performed by all Muslims facing the qibla). These prayers are considered the second of the five pillars upon which the Islamic doctrine is built and they play a pivotal role in the life of every believer, granting them access to God. It is only natural to wonder then, what kind of ewers were in use to perform these daily ablutions in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. Clearly, their style and form must have been dictated by elements like status and wealth. Due to numerous Muslim jurists' fatwas that barred the use of gold and silver vessels, it is safe to assume that ruling elites adhered to such imposition. Therefore, the easiest solution to vaunt their status and gain recognition was to commission vessels inlaid with precious and semi-precious metals, often bearing their names. Under these circumstances, the function of the present lot is all the more special. Boosting its holy charge by avoiding the presence of any figural motif and multiplying the auspicious, benedictory inscriptions throughout its body, this ewer must have probably been commissioned to perform daily ablution rituals by a high-society member of the Ghurid court or Seljuq atabeg.

(Quantity:1)

Dimensions: 30.4cm high

Sold for £11,250

Includes Buyer's Premium

Do you have an item similar to the item above? If so please click the link below to request a free online valuation through our website.